By striking down a 40-year-old legal precedent that allowed unelected and unaccountable federal bureaucrats to interpret ambiguously worded statutes as they see fit, the Supreme Court jerked the chain of an administrative state that had become accustomed to riding roughshod over the Constitution’s separation of powers.

The high court’s 6-3 ruling in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo jettisoned what was known as Chevron deference, which required courts to defer to federal agencies’ interpretation of unclear statutory text if the interpretation is merely “reasonable.” (Chevron refers to the 1984 Supreme Court opinion in Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Fund.)

By ceding such vast authority to the permanent bureaucracy, Chevron deference helped stack the deck against anyone who had run afoul of the policy preferences of ever-more powerful federal agencies. Now, federal judges can no longer defer to entrenched bureaucrats to determine what Congress intended in crafting a law; the courts themselves must make that call.

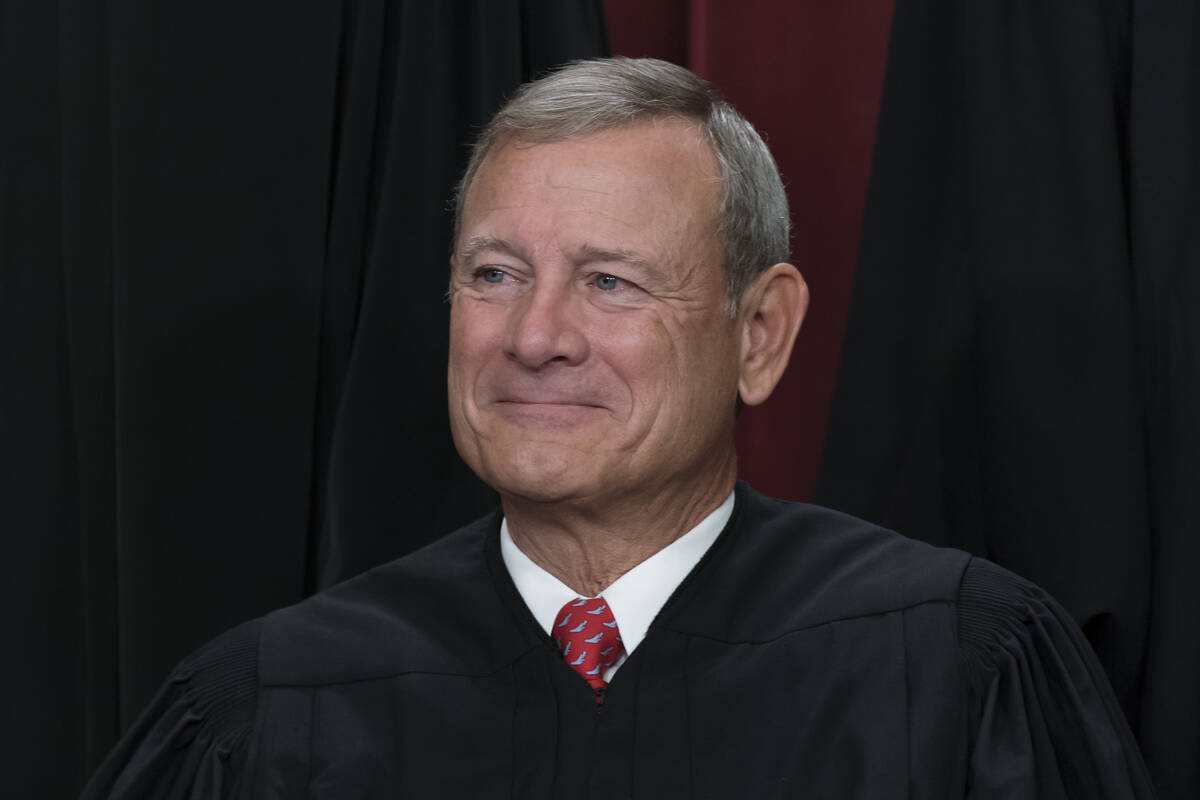

Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts noted that a doctrine that allows bureaucrats to make such distinctions “is misguided because agencies have no special competence in resolving statutory ambiguities. Courts do.”

It is also true that bureaucrats in regulatory agencies are not disinterested parties. They may be faceless, but they have a stake in expanding the agency’s power where they spend their professional careers and will find it hard to resist the temptation to interpret a statute in such a way that it further empowers that agency. Furthermore, people who choose careers in federal regulatory agencies are likely to be ideologically predisposed to support rules and regulations that strengthen the hand of the regulatory state.

Concurring with the majority, Justice Clarence Thomas added that “by tying a judge’s hands, Chevron prevents the judiciary from serving as a check on the executive.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch noted that Chevron “has led us to a strange place. One where … the scales of justice are tilted systematically in favor of the most powerful, where legal demands can change with every election, even though the laws do not, and where the people are left to guess about their legal rights and responsibilities.”

As Gorsuch suggests, the real-world consequences of a doctrine that allowed agencies to regulate vast swaths of American life unencumbered by checks on their authority are profound. In an amicus brief urging an end to Chevron deference, the Washington Legal Foundation and the Independent Women’s Law Center underscored the harm the doctrine wrought throughout society.

“Recently, agencies have tried to rewrite the federal student loan program, attempted to bar landlords from collecting rent on their properties and forced workers nationwide to get a vaccine,” the brief said. “Each time a regulatory agency far exceeded its statutory power because it felt emboldened by Chevron.”

Recognizing the blow the court’s ruling had dealt the regulatory state, Justice Elena Kagan was scathing in her dissent, saying the majority had replaced a rule of “judicial humility” with one of “judicial hubris.”

“In one fell swoop, the majority today gives itself exclusive power over every open issue — no matter how expertise-driven or policy-laden — involving the meaning of regulatory law,” she wrote.

“The court has substituted its own judgment on workplace health for that of the Occupational Health and Safety Administration; its own judgment on climate change for that of the Environmental Protection Agency; and its own judgment on student loans for that of the Department of Education,” Kagan added.

Putting weighty constitutional issues aside for a moment, the underlying assumption in Kagan’s remarks is that “expertise-driven” wisdom resides in the corridors of federal agencies. Recent experience calls that into question. From public health agencies’ response to COVID-19 with lockdowns, school closures and mandates for masks and vaccines, to climate regulators’ micromanaging people’s selection of household appliances and personal transportation, “experts” are rapidly falling out of favor with much of the public.

The mighty edifice that was Chevron deference was brought low by a small, slimy fish: the herring. A rule issued by the National Marine Fisheries Service charging commercial herring vessels operating in the North Atlantic up to $700 daily per vessel to monitor herring catches threatened to bankrupt a New Jersey fishing operation. The fishermen sued, saying NMFS had no authority to impose such a charge. That authority was Chevron deference. Expressing his view on Chevron a year ahead of the Supreme Court’s ruling, Justice Gorsuch stated: “At this late hour, the whole project deserves a tombstone no one can miss.”

That tombstone now stands.

Bonner Russell Cohen is a senior policy analyst with the Committee for a Constructive Tomorrow. He wrote this for InsideSources.com.